The anatomy of a patent litigation target

Intellectual property (IP) protection can be a vital part of a company’s journey from young upstart to billion-dollar behemoth, safeguarding all its technologists’ hard work while adding to the company’s value for investors or would-be acquirers.

But as we’ve seen countless times through the years, IP can also be weaponized.

Patent wars have been a mainstay of the modern technology era, with some of the world’s biggest companies embroiled in high-profile tête-à-têtes, from Apple vs. Samsung, Qualcomm and Nokia, to Google vs. Sonos, Twitter vs. IBM and many more. While some of this patent palaver might well stem from genuine IP infringements, there are many examples of patents being misused purely for financial gain.

This is one fear that’s emerging in the aftermath of OpenText’s $6 billion acquisition of Micro Focus, a deal that closed six months ago. We go into the full details of that story here. But the long and short is that OpenText picked up thousands of granted and pending patents through the acquisition; Micro Focus is now giving up its membership of the anti-patent troll membership organization LOT Network; and many are left wondering what happens next. OpenText is no stranger to patent assertion, and it has already been accused of behaving like a patent troll in the wake of its 2019 acquisition of data security firm Carbonite — a deal that has led to ongoing patent litigation proceedings against CrowdStrike, Kaspersky, Sophos, and Trend Micro.

This all leads to one question: what does a patent litigation target look like in 2023? And is there anything in particular that might make one company more susceptible to lawsuits than another?

NPE threat

The cost that non-practicing entities (NPEs), or “patent trolls,” have on innovation is sizeable, particularly impacting startups and scale-ups manoeuvring through the world of R&D, although long-established billion-dollar companies are far from immune, too.

A report published earlier this year by LOT Network, conducted by IP consultancy Hightech Solutions (HTS), delved into exactly this. The NPE threat: patent sources and litigation target charactertistics explored litigation activity around NPEs from 2017 to 2022, using data provided by Unified Patents related to more than 6,000 defendants sued by NPEs over the period.

As you might expect, the likes of Google, Amazon, Samsung, and Apple feature highly in the list of defendants most frequently targeted in patent litigation. However, part of the report’s remit was to discover to what extent NPEs pose a threat to smaller companies — those on the cusp of getting big that may have a lot on the line. These firms might not always have sizeable legal resources at their disposal, either.

The data suggests that while “legitimate” patent litigation by operating companies has declined a little in recent years, those instigated by NPEs has “increased steadily,” due mostly to the number of patent assets “for sale on the open market and availability of litigation funding.”

“It’s quite common for NPEs, rather than to fund or finance themselves, [to connect] with a litigation financing entity that essentially pays for the litigation and then gets a cut on the assertion,” IP attorney Patrick McBride, who most recently headed up IP programs at Red Hat, explained to TechCrunch. “And as you might imagine, that changes the game quite a bit, because the NPE has significant financial resources backing them and what they’re trying to do.”

Roughly 60% of all patent litigation last year stemmed from NPEs. But the characteristics that make a company “more or less likely” to be targeted by a frivolous patent lawsuit, as identified in the report, makes for interesting reading.

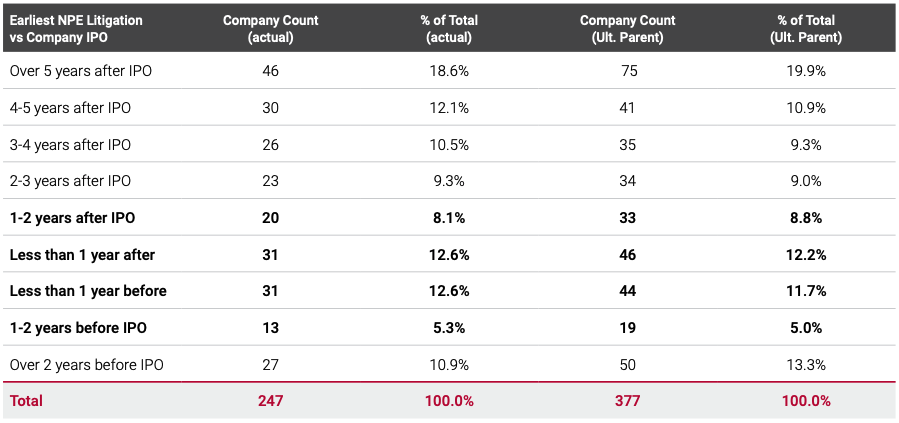

The report starts with a hypotheses that NPEs could be motivated by timings related to a company’s IPO. For example, startups approaching a public listing will be keen to settle quickly, while those that have just completed an IPO may have extra capital at their disposal.

Of the 247 companies it identified from NPE litigation targets that went public from 2012 to 2022, 30 percent of the earliest litigation took place four years or more after the date of the IPO. But by contrast, 39 percent of the NPE litigation took place in the two years before and after an IPO.

The report noted:

This finding gives support to the hypothesis we were exploring, and means that the period before and after an IPO is a time of elevated risk that a firm will become the target of one or more NPE lawsuits.

Select NPE Litigation (2017 – 2021) and Financial Data (IPOs from 2012 – 2022) Image Credits: HTS / LOT Network

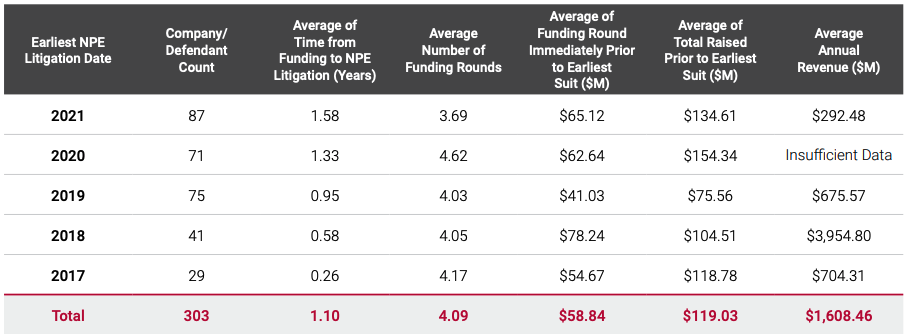

The report also suggested that NPEs might take into account funding raised by its targets, with the average number of rounds raised sitting at nearly four — this means that somewhere around Series C to D stage is attractive to NPEs, with the average funding amount raised prior to the earliest litigation sitting at $65 million.

The report added:

This all makes sense, in that, in business, it is always more attractive to sue a target that has deep pockets, than one known to be scarce of financial resources.

Summary of NPE Lawsuits Against Private Companies By Earliest NPE Litigation Date (Funding Rounds

Announced 2017 – 2022) Image Credits: HTS / LOT Network

This data might not tell the full story, of course. Not all litigation threats makes it into the public sphere; some might get settled at the earliest possible stage before attracting any attention. But it still supports the notion that patent trolls adopt a fairly targeted approach to their litigation endeavors.

“NPEs are attracted to money and they want easy money,” McBride said. “They’re attracted to entities with products in the marketplace that they can analyse and at least make a colorable claim that they are covered by their patents. The more your products are in the marketplace, visible to consumers and such like, the more likely you are to be the target of an assertion.”

Tears of a cloud

There are some real-world examples that help to illustrate some of these data points. This includes Cloudflare, which is presently in the midst of fighting a second round of patent litigation that kicked off in 2021 — roughly two years after the company went public.

However, the web infrastructure giant was initially targeted by a different patent troll in 2017, exactly two years before going public. Rather than acquiescing, Cloudflare went on the offensive and launched a crowdsourced campaign called Project Jengo. This was in response to Blackbird Technologies, a law firm that had managed to acquire dozens of patents before filing lawsuits against several companies, including Cloudflare.

Project Jengo was (and still is) pitched as a “contest,” with Cloudflare offering financial rewards to people who help conduct research around prior art to help fight its case. Cloudflare emerged victorious in 2019 just before listing on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), but two years later it was targeted by yet another patent troll. And although some 90% of those assertions made against it were thrown out earlier this year, Cloudflare will have to face some of these claims in court later this year.

Cloudflare general counsel Doug Kramer acknowledged that pre-IPO startups might seem to be a more alluring target for NPEs, but it’s maybe not quite as clear-cut as that.

“I’m not sure we’ve seen a clear strategy or targeting in the flood of threatening letters and threatened lawsuits pursued by patent trolls,” Kramer explained to TechCrunch. “Once an NPE gets hold of a patent, it will often send letters to everyone who could plausibly be sued for infringement under that patent — including very early-stage companies, or even a company that purchases a retail product off the shelf made by a company that the NPE may allege is infringing. They cast a wide net and see what they can reel in.”

The alternative to fighting back, according to Kramer, would likely have been to settle for a “low six-figure” sum. However, the bigger concern here was about setting a precedent, encouraging more frivolous claims further down the road.

“We really saw the main risk was that we’d be shovelling more coal into the engine of this roaring locomotive,” Kramer said. “We didn’t want to perpetuate that system, and thought there was a way that we could pay more in the short term and try to set up ourselves, and the industry generally, in a better position for the long term.”

The fact that Cloudflare is facing a second round of patent litigation might suggest that the company’s combative tactics didn’t work as a deterrent. But Kramer argues that it’s more about reducing rather than completely removing the chances of being targeted.

“We definitely think Project Jengo can deter future trolls, both against Cloudflare specifically and against companies generally,” he said. “Deterrents are successful if they diminish the flow of cases, even if not eliminating them entirely. And we’re definitely aware of some claims or threats of claims that were withdrawn when trolls became aware of our practices.”

Vulnerable

Autonomous vehicle startup Oxa (formerly Oxbotica) is one startup that’s approaching a stage that patent trolls might start paying attention to it, having recently closed a $140 million Series C round of funding. The company has filed for around 8 patents itself, with one granted at the time of writing.

Alex Tame, head of licensing and IP management at Oxa, says that although he’s not anticipating patent litigation in the immediate future, things could change as its profile grows.

“As a small company in the U.K., we’re probably not really on the radar for many of the ‘problem’ companies out there,” Tame said. “As we start to grow and our brand starts to get a bit more kudos, we’re going to be on someone’s radar somewhere.”

AI companies, including startups similar to Oxa that are working on autonomous vehicles, have been ripe for acquisition these past few years. Part of this has been driven by the need for top technical talent, but IP has also been a central component. When Amazon, for example, doled out a reported $1.2 billion for self-driving automobile startup Zoox back in 2020, it scooped up more than 150 patents, spanning cruise control, signalling, and driver assistance technologies, according to Forbes at the time.

While there hasn’t been a great deal of IP litigation in the AI realm generally, we are still in the relatively nascent phase of a fast-growing AI revolution, and things can change quickly as more players look to assert their authority (and IP) over rivals. ChatGPT developer OpenAI is currently in the process of trademarking “GPT” with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), a harbinger perhaps of what’s to come down the road for startups, scaleups, and enterprise behemoths trying to get their slice of the trillion-dollar AI pie.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re about to see a maelstrom of lawsuits and counter lawsuits, but with the AI hype train gaining steam, companies will at least start to get defensive with their IP measures so that they have some basis for protecting themselves. This isn’t limited to patents, but trademarks, copyright, and all the rest.

This is partly why one of Tame’s first tasks when he joined Oxa in 2019 was to set the company up with membership in LOT Network, the nonprofit coalition that protects member companies by automatically cross-licensing their patents if they fall into the hands of a patent assertion entity (PAE — a similar concept to an NPE, which LOT defines as an entity that derives more than half of its income from patent enforcement). LOT counts thousands of members, including some of Oxa’s deeper-pocketed rivals.

“We aren’t in an industry that — at the moment — is going to be litigious,” Tame said. “We’re not an industry that’s going to start picking fights with each other, though that may come later. You look at who the members are of the LOT Network, and most of our competitors are in the network. So it was a bit of a no brainer — if we joined the LOT Network, we get some protection from [the likes of] Google and Uber and Aurora.” (Though this protection only extends to scenarios where LOT members’ patents fall into the hands of a NPE/PAE).

While there might not always be a cogent or consistent strategy in the patent troll playbook, it appears that there is something of a sweet spot in terms of what an ideal litigation or licensing target looks like. Sure, Google or Intel might be juicy targets, but they’re also well-resourced and well-versed in addressing litigation.

“The thing to understand about NPEs is they are not about the merits of their invention, they are about negotiating leverage to maximise the money they get — that’s the game they are playing,” McBride said. “And so when you are a pre-IPO company, or you are a small company wishing to be privately acquired, you are in a vulnerable state.”

The idea is that any pre-IPO company that might be subject to due diligence, either ahead of a public-listing, funding round, or potential acquisition, will want that inspection to go as smoothly as possible. Any lingering litigation, spurious or not, is a major red-flag in the due diligence process. Thus patent trolls could be attracted to such scenarios, since the startup might be a little more willing to settle the case.

“I have done due diligence on companies that were hoping to be acquired, they were subject to an NPE assertion or litigation and that killed the deal,” McBride said. “The NPEs know this, and specifically time their attacks for just such an event.”