NYC gig workers need help accessing safe e-bikes amid lithium battery fires

The sight of bike delivery workers hustling through the streets of New York — oven mitts duct-taped to their handlebars, insulated pizza delivery bags strapped above the back tire — has been a staple long before the introduction of e-bikes and food delivery apps. Delivery workers are so integral to the landscape that it’s often easy to take them for granted. But New York wouldn’t be the city that never sleeps if its denizens couldn’t get an order of chicken wings and pork fried rice delivered at three in the morning.

As cost of living skyrockets and demand for food delivery via apps like Grubhub, DoorDash, Uber Eats and Relay increase, delivery workers have to pick up and drop off orders at a much faster clip. This increased pressure comes as electric bikes, scooters and mopeds become more popular and accessible, making the jobs of delivery workers easier.

The downside? Fires caused by lithium-ion batteries are tearing through the city. And deliveristas, the gig labor force largely made up of immigrant men from Spanish-speaking countries, are increasingly at risk of falling victim to such fires.

As if they didn’t have enough to worry about, given bike theft, assaults, reckless NYC drivers, rain, snow, hail, sleet, heat and no access to public toilets.

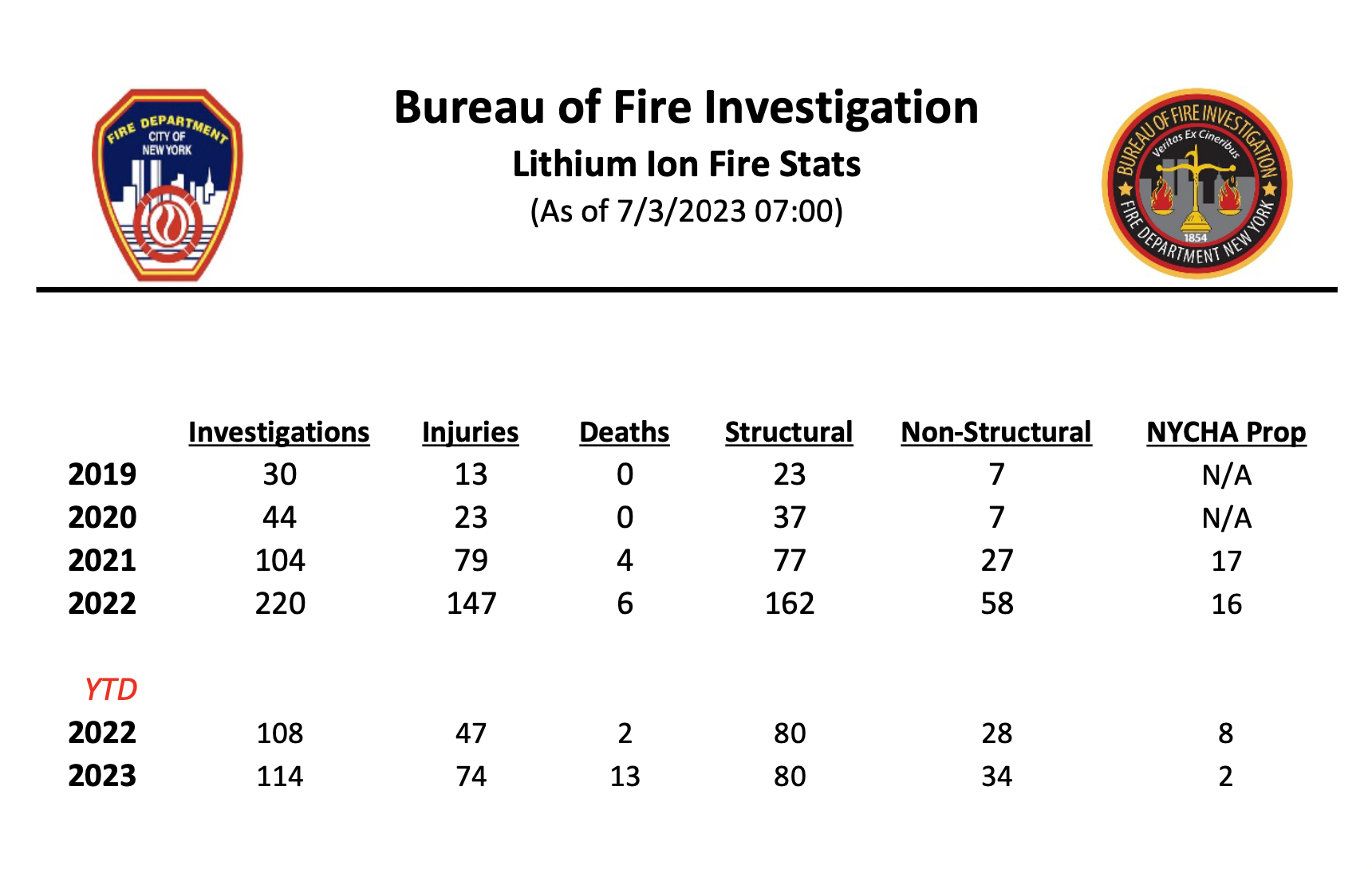

In New York City, lithium-ion fires caused by micromobility vehicles have more than doubled each year from 2020 to 2022, according to Fire Department of New York (FDNY) data. In 2022, there were 220 fires that resulted in 147 injuries and six deaths, up from 104 fires, 79 injuries and four deaths in 2021 and 44 fires, 23 injuries and zero deaths in 2020. This year, there have already been 114 investigations into lithium-ion fires, 74 injuries and 13 deaths, as of July 3, 2023. While the FDNY doesn’t break down stats into what types of devices caused the fires, 80 of the 2023 fires occurred in structures like homes, buildings and offices.

Bureau of Fire Investigation lithium-ion battery fires. Image Credits: Fire Department of New York

Of course, not all of these fires can be tied to the on-demand delivery industry. A recent deadly blaze that killed four people in Chinatown started from an e-bike store. But deliveristas seem to be at a higher risk than the average e-bike owner.

Gig work is low-income work, which means deliveristas are more likely to buy cheap e-bikes and batteries that aren’t certified. They also spend hours a day riding bikes all over the city, which means more wear and tear and the possibility of damaging the batteries. And when it comes to range management, many deliveristas don’t have safe, secure places to charge, and may end up charging them in their apartments, perhaps even overnight, which can lead to overheating.

In recent months, Mayor Eric Adams has announced an action plan to combat lithium-ion battery fires, which includes funding battery storage and charging hubs, pushing for incentives and rebates to buy better bikes and raising awareness on the issue. The city has also passed two crucial laws; the first, which recently went into effect, prohibits the assembly or reconditioning of lithium-ion batteries using cells removed from used storage batteries. The second, which goes into effect in September, involves banning the sale, lease or rental of micromobility devices and batteries that fail to meet recognized safety standards.

As gig workers scramble to get their hands on certified vehicles, they say the app companies should be responsible for helping them out.

William Medina, a member of Los Deliveristas Unidos, a collective of New York City’s delivery workers, told TechCrunch he thinks “these multimillion-dollar delivery companies…should implement some support to workers to make sure they’re buying safe batteries.”

“They don’t assume any responsibility when there are fires, accidents or deaths,” said Medina, noting that deliveristas were the ones bringing food and medicine to people throughout the pandemic, and that they keep NYC moving as a 24-hour economy.

The average cost of a certified e-bike that’s used by delivery workers is around $1,500, according to workers TechCrunch spoke to. On top of that, the cost of maintenance, charging, insurance and battery replacements could set a worker back another $450 to $550 annually. Medina says a typical six-day work week in NYC might bring in $700 to $800, and that’s before expenses and taxes.

Gig workers are classified as independent contractors, not employees. As a result, app companies are careful with how much support they provide to their workers and in what ways, lest they creep into employer territory.

Veena Dubal, a professor of law at the University of California College of the Law, San Francisco, says foisting the costs of doing business onto “the workers who create the most value for the firms,” is one way to avoid employer responsibility.

“The companies are worried that if they provide charging stations or safe batteries, this will not only increase their labor costs, but it will also be indicative of their status as employers — providing the instrumentalities of work,” Dubal told TechCrunch via email. “This is yet another example in which the dangers of this work are unjustly borne by low-income, racial minority workers, who may lose life or limb to earn a sub-minimum wage.”

What UberEats, DoorDash and Grubhub are doing to help

A screenshot of an email DoorDash sent to Dashers with e-bike fire safety tips. Image Credits: DoorDash

DoorDash and Uber both separately donated $100,000 to the FDNY Foundation to support its efforts to increase fire safety messaging, education and outreach. Both companies are also supporting the Equitable Commute Project (ECP), which offers an e-bike trade-in program. They each donated $200,000 to the ECP, according to Melinda Hanson, co-founder of the organization.

As part of the trade-in program, delivery workers can trade their uncertified e-bike, e-scooter or e-moped for a discounted UL2849-certified Tern Quick Haul with two Bosch batteries. While the Tern is an amazing bike that’s well-suited for delivery, the prospect might not appeal to workers who would still need to shell out for the cost of the bike — $2,200 plus tax. While that’s about 40% off the retail price of that bike, it’s still not exactly within the range of a deliverista’s budget.

The problem is that quality e-bikes, even discounted ones, have to compete with the sub-$100 bikes that deliveristas can buy from China or on sites like Alibaba, which much better suit a delivery worker’s pre-tax income of no more than $800 a week, according to workers who spoke to TechCrunch.

As one Reddit user put it: “Realistically, is a delivery worker going to turn in their uncertified e-bike and pay $2,200+ tax for a certified one in the name of safety?”

That said, ECP works with Spring Bank to give workers access to a low-cost, 12-month loan, even if the worker has no credit score, so that workers can buy their bike from ECP through low monthly payments.

DoorDash told TechCrunch it also works to raise awareness, regularly sending out battery fire safety tips. The company’s landing page for bike Dashers also includes links to resources like battery charging and storage tips and where to find rebates and incentives.

DoorDash also partners with e-bike companies Dirwin and Zoomo to help Dashers get access to safe bikes. Dirwin offers 30% off the purchase of an e-bike, helmet and front basket, as well as a free accessory package that includes a cell phone mount, water bottle holder, tire pump and sunglasses. That’s available for financing at around $33 per week or a total price of around $1,600 for everything.

Zoomo’s partnership with DoorDash gives Dashers in NYC $100 off its “Boost” plan, which costs $199 per month for an e-bike subscription. Included in that subscription is access to any of Zoomo’s e-bikes, servicing, theft protection and a spare battery.

Uber is also working with Zoomo on an identical partnership offering. The companies will also work together on a trade-in program that will give couriers with uncertified e-bikes “a significant monetary amount” toward a new e-bike when they trade it in. Uber told TechCrunch it plans to invest close to $1 million collectively in its pilots with Zoomo and ECP and its FDNY donations.

Zoomo said thousands of couriers have signed up through its partnerships with UberEats and DoorDash.

Grubhub is currently doing a six-month pilot with Joco, a docked, shared e-bike operator that services gig workers, to give at least 500 gig delivery workers per month free access to Joco’s bikes. Joco’s fleet of 1,000 bikes can be found at 55 stations across Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens. Grubhub also sponsored a Joco rest stop in downtown Manhattan where workers can take breaks, use the bathroom, charge their phones and switch out dead batteries with fully charged ones.

Since the pilot launched in mid-June, the companies say they’ve had about 1,000 unique visitors to the hub, but neither would stipulate exactly how many riders have taken advantage of this offer for free e-bike access. Grubhub also didn’t say whether it has plans to extend the pilot beyond six months.

The company also told TechCrunch in April it was actively working to establish a battery recycling program to take in non-certified e-bikes but did not provide any updates on that initiative.

Relay, a local NYC gig delivery company, would not answer TechCrunch’s questions about how it is helping delivery workers.

What could gig companies be doing better?

The main causes of e-bike, e-scooter and e-moped battery fires are: Cheap vehicles and batteries made with low-quality manufacturing processes and budget materials; overcharging in crowded conditions among other devices charging; damage to the battery; and overuse. All of these are common among delivery workers, and the issue is compounded because it’s New York City, where everyone lives in cramped apartments so a blaze in one unit spreads quickly to the next.

Aside from measures that the city is taking to ensure the safety of its labor force, advocates and workers say gig companies could be doing more to support solutions. After all, delivery workers are the backbone of their entire enterprises, and if they aren’t going to get fair working conditions, they could, at the very least, be aided in not causing — or dying in — a lithium-induced blaze.

For a start, the delivery companies could create a standard for e-bikes that their delivery workers use, similar to how Uber and Lyft have a standard for the cars allowed to be used for ride-hailing.

Uber and Lyft also pay into the Black Car Fund in NYC, which helps drivers get access to benefits like Workers’ Compensation. The delivery companies, the city and restaurants could create a similar fund that goes toward giving workers access to affordable and safe batteries.

Some workers told TechCrunch it would make sense for companies and the government to fund a battery buy-back program because replacing batteries might be cheaper than subsidizing entire e-bikes. In fact, a bill has been introduced to the NYC Council that would set up a program to provide new batteries for e-scooters and e-bikes at reduced or no cost, or in exchange for used batteries.

Uber, Grubhub and DoorDash could also help fund better charging and storage infrastructure — places where workers can lock up their bikes and charge them safely. Other options include piloting battery swapping services like those offered by Taiwan-based Gogoro and Berlin-based Swobbee.

A study done by WXY Studio, and ironically commissioned by Uber, found that better pay could also help address the battery fire issue because workers would be able to afford better-quality bikes. The irony is that Uber, as well as DoorDash and Grubhub, is suing the city for mandating a guaranteed minimum wage of $18 per hour for delivery workers, a wage that many labor advocates argue isn’t even a living wage after expenses.

Gig companies can also offer incentives for delivery workers who purchase UL-certified e-bikes and other micromobility devices. Uber currently claims to offer drivers $1 per trip in an electric vehicle, so the precedent has already been set. Apps could also potentially provide loans to delivery workers or subsidize leases and rent-to-own programs.

Finally, they can raise awareness. Companies should be leading the charge with informing deliveristas of the risks, how to stay safe, where they can find good deals on certified bikes and what laws or resources are in place.